| 本条目属于 |

| 美利坚合众国宪法 系列 |

|---|

|

| 序言和正文 |

| 修正案 |

|

|

| 历史 |

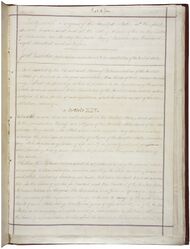

美利坚合众国宪法第十四条修正案(Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution)于1868年7月9日通过,是三条重建修正案之一。这一修正案涉及公民权利和平等法律保护,最初提出是为了解决南北战争后昔日奴隶的相关问题。修正案备受争议,特别是在南部各州,这些州为了重新加入联邦而被迫通过修正案。第十四条修正案对美国历史产生了深远的影响,有“第二次制宪”之说[1]:207,之后的大量司法案件均是以其为基础。特别是其第一款中“不得拒绝给予任何人以平等法律保护”的一项,是美国宪法涉及官司最多的部分之一,它对美国国内的任何联邦和地方政府官员行为都有法律效力,但对私人行为无效。有关此修正案的法律解释和应用在美国国内一直受到争议,自由派通常会接受法院的裁决,并支持通过法院来推翻被指违反民权法律等行为。

修正案的第二至四款极少在法律诉讼中引用,第五款赋予国会执法权。第一款包括了多个条款:公民权条款、特权或豁免权条款、正当程序条款和平等保护条款。公民权条款对公民权作出了宽泛的定义,推翻了美国最高法院在1857年斯科特诉桑福德案案中裁定非洲奴隶在美国出生的后代不能成为美国公民的判决。特权或豁免权条款经解读后的实际应用情况也很少。

正当程序条款禁止各州未经正当法律程序而剥夺任何人的生命、自由或财产。这一条款经联邦司法部门的应用,把权利法案中的大部分内容应用到了各州,并且要求各州的法律必须满足实质性和程序性的正当程序要求。

平等保护条款要求各州对其管辖范围内的任何人以平等法律保护。这一条款在1954年布朗诉托皮卡教育局案后成为此修正案的法理基础,美国最高法院在该案中判决种族隔离制度违宪,之后又在其他多个案件裁决中推翻了针对不同群体人士的任何不合理或不必要的歧视和种族隔离的法律。美国自由派组织和民间团体一直希望通过平等权利修正案取代此修正案,因为此修正案的内容仍有缺撼,但最终该修正案在1982年失效而搁置。布朗诉托皮卡教育局案后,美国最高法院陆续以此修正案为基础进行宪法解释,并实际上把涉及公民权利的法律进行立法,包括1973年有关堕胎权利问题的罗诉韦德案、有关2000年美国总统选举最终结果的布什诉戈尔案及2015年裁定美国同性婚姻全国合法化的奥贝格费尔诉霍奇斯案等拥有里程碑性质的判决,均是以这一条款为基础。

法案正文

|

中文译本

|

提出和批准

国会提出

在南北战争的最后几年,以及随之而来的重建时期,联邦国会逐渐就数百万通过1863年解放奴隶宣言和1865年第十三条修正案获得自由的前黑人奴隶的权利问题进行反复辩论,其中后者正式确立废除了奴隶制。然而随着第十三条修正案在国会通过,共和党开始担心国会中被民主党主控的南方州议员席位将大幅增长,因为这些州原本大都有数量庞大的黑奴。而根据原宪法第一条中的五分之三妥协,每名黑奴按五分之三个自由人计算,而在第十三条修正案通过后,所有黑奴都成了自由公民,所以无论获得自由的黑人是否会投票,根据各州人口数分配的联邦众议院议席都将出现戏剧性的增长[4]:22[5]:111。共和党希望通过吸纳和保护新增黑人选民的选票来抵消民主党的增长。[4]:22[5]:112[6]

1865年,国会通过了一项在后来成为《1866年民权法案》的提案,它确保了个人的种族、肤色或之前是否曾作为奴隶及受到强制劳役等因素不会成为其能否获得公民权的先决条件。该法案还保证法律上的利益均等,这直接打击了内战后南方多个州所通过的黑人法令。黑人法令试图通过其他的一些方式,表面看来并未恢复奴隶制,但实际效果却在许多方面导致黑人回到以前身为奴隶时的处境中。如限制其活动,迫使他们签订整年时长的劳役合同,禁止他们拥有枪支,以及阻止他们到法院起诉或作证等。[7]:199-200但是,《1866年民权法案》受到了安德鲁·约翰逊的否决,他是一位决不妥协的白人至上主义者[4]:21-22。1866年4月,国会通过投票推翻了总统的否决,法案正式成为法律,而这一推翻也增强了共和党的信心,他们决心给黑人权利增加宪法级别的保障,而不仅依靠难以长久的政治多数优势[4]:22-23。再者,甚至一些支持民权法案目标的共和党人也怀疑国会是否的确拥有制订这一法案的宪法权利[8][9]。

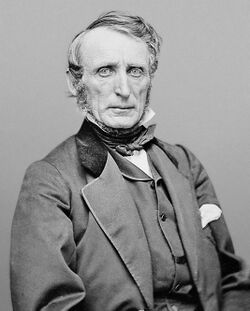

修正案前后起草了超过70份草案[10]。其中在1865年末由美国国会重建联合委员会提出的一份草案中,表明一州如因种族而禁止公民投票,那么在根据该州人口总数计算国会议席数时,这部分公民的人口数也不会计入[7]:252。这一草案在联邦众议院获得通过,但在联邦参议院受阻,以马萨诸塞州联邦参议员查尔斯·萨姆纳为代表的联盟认为该提案是个“错误的妥协”,而民主党参议员则反对黑人权利[7]:253。国会于是转而考虑俄亥俄州联邦众议员约翰·宾汉姆提出的草案,其内容允许国会对“所有公民的生命、自由和财产”提供“平等保护”,但这份草案没得获得众议院批准[7]:253。1866年4月,联合委员会向国会提交了第三份提案,其内容经仔细协商,纳入了第一和第二份提案的元素,并提出了前美利坚联盟国债务及其支持者投票权的解决方案[7]:253,当中的措辞还在众议院和参议院的多次差距很小的投票中作了进一步修改[7]:256。这个妥协版本最后在参众两院获得了通过,两党态度径渭分明,共和党支持,民主党反对[4]:25。

激进派共和党人对他们确保了黑人民权感到满意,但对修正案没能确保黑人的政治权利,特别是投票权感到失望[11]。在这些失望的激进派共和党领袖中,来自宾夕法尼亚州的众议员撒迪厄斯·史蒂文斯表示:“我觉得我们有义务对这古老建筑最糟糕的一部分加以修补,然而它却饱受专制主义暴风雨、霜冻和风暴的洗礼。”[11][12]:1501-1502废奴主义者温德尔·菲利普斯则称修正案是一个“致命而彻底的投降”[12]:1501-1502。这个问题之后将在第十五条修正案得到解决,第39届美国国会于1866年6月13日提出了第十四条修正案。

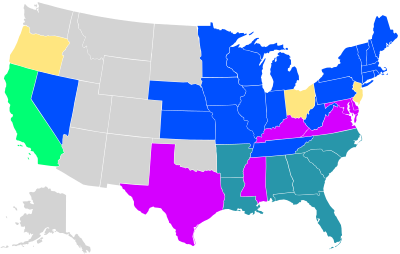

各州批准

在修正案生效前,于1866至1868年批准的州

在修正案生效前,起初拒绝,之后再于1868年批准的州

在修正案生效后,起初拒绝,之后再于1869至1976年批准的州

在修正案生效后,于1959年批准的州

起初批准,后又撤消批准,再又重新批准的州

1868年尚未成为美国一州的领地

第十四条修正案的批准备受争议:除田纳西州外,其它所有南方州议会均拒绝批准。这导致了国会于1867年通过了重建法案,该法案直接授权军队接管这些州政府的职权,直到新的民选政府建立并且第十四条修正案通过为止[13]。

包括菲利普斯在内的废奴主义领袖批评修正案认可一州有权基于种族来拒绝公民的投票权[7]:255。第二款中提到的“男性居民”字眼是宪法中首次提及性别,这受到了包括苏珊·安东尼和伊丽莎白·卡迪·斯坦顿在内的女性选举权积极分子的谴责,早在内战前和内战期间,女性选举权运动就与废奴主义运动结成了统一战线。修正案中把黑人民权与女性民权分离的做法,导致两个运动从此分裂达数十年之久。[7]:255-256

1867年3月2日,国会通过立法,规定任何原美利坚联盟国成员州必须先批准第十四条修正案,然后才可以恢复在国会中的议席。[14]

1868年7月9日,南卡罗莱纳和路易斯安那批准了修正案,使批准州的总数达到宪法第五条规定四分之三多数的28个(美国当时有37个州)[15][16],这28个州如下:

- 康涅狄格州:1866年6月25日

- 新罕布什尔州:1866年7月6日

- 田纳西州:1866年7月19日

- 新泽西州:1866年9月11日(1866年9月11日,新泽西州议会试图从1868年2月20日起撤消起批准,理由是该修正案在国会通过时存在程序性问题,其中包括某些州当时被非法地剥夺了在众议院和参议院的代表权[17]。新泽西州长于3月5日否决了该州的撤消,州议会又于3月24日推翻了州长的否决。)

- 俄勒冈州:1866年9月19日

- 佛蒙特州:1866年10月30日

- 俄亥俄州:1867年1月4日(1867年1月4日,俄亥俄州通过一项决议,据称要在1868年1月15日撤回其批准。)

- 纽约州:1867年1月10日

- 堪萨斯州:1867年1月11日

- 伊利诺伊州:1867年1月15日

- 西弗吉尼亚州:1867年1月16日

- 密歇根州:1867年1月16日

- 明尼苏达州:1867年1月16日

- 缅因州:1867年1月19日

- 内华达州:1867年1月22日

- 印第安纳州:1867年1月23日

- 密苏里州:1867年1月25日

- 罗德岛州:1867年2月7日

- 威斯康星州:1867年2月7日

- 宾夕法尼亚州:1867年2月12日

- 马萨诸塞州:1867年3月20日

- 内布拉斯加州:1867年6月15日

- 艾奥瓦州:1868年3月16日

- 阿肯色州:1868年4月6日,该州曾于1866年12月17日否决过这一修正案

- 佛罗里达州:1868年6月9日,该州曾于1866年12月6日否决过这一修正案

- 北卡罗莱纳州:1868年7月4日,该州曾于1866年12月14日否决过这一修正案

- 路易斯安那州:1868年7月9日,该州曾于1867年2月6日否决过这一修正案

- 南卡罗莱纳州:1868年7月9日,该州曾于1866年12月20日否决过这一修正案[15][16]

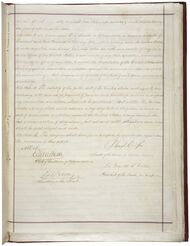

1868年7月20日,美国国务卿威廉·H·苏厄德证实如果新泽西和俄亥俄两个州的批准并没有撤消而仍然有效的话,修正案将成为宪法的一部分并开始正式生效。并且假定认为以前反对此修正案的州政府均已重新组建并推翻之前的反对意见[18]。国会也在次日发表声明称修正案已经成为宪法的一部分,并要求国务卿正式颁布[19]。

与此同时,亚拉巴马州于1868年7月13日批准了修正案,同日该州州长同意了这一批准;而之前曾在1868年7月21日否决过修正案的乔治亚州于1868年7月21日批准了修正案[15][16]。于是到了7月28日,国务卿正式宣布修正案成为宪法的一部分,部分州对批准的撤消均不生效[19]。

民主党赢得俄勒冈州的立法选举后于1868年10月15日撤消了该州之前对修正案的批准,但由于为时已晚,这一撤消受到了忽略。第十四条修正案之后获得了1868年时美国全部37个州的批准,其中俄亥俄州、新泽西州和俄勒冈州都是在撤消批准后重新批准。[20]之后批准的各州和批准日期如下:

- 弗吉尼亚州:1869年10月8日,该州曾于1867年1月9日否决过这一修正案

- 密西西比州:1870年1月17日,该州曾于1868年1月31日否决过这一修正案

- 得克萨斯州:1870年2月18日,该州曾于1866年10月27日否决过这一修正案

- 特拉华州:1901年2月12日,该州曾于1867年2月7日否决过这一修正案

- 马里兰州:1959年4月4日,该州曾于1867年3月23日否决过这一修正案

- 加利福尼亚州:1959年3月18日

- 俄勒冈州:1973年,该州曾于1868年10月15日撤消了对这一修正案的批准

- 肯塔基州:1976年5月6日,该州曾于1867年1月8日否决过这一修正案

- 新泽西州:2003年,该州曾于1868年2月20日撤消了对这一修正案的批准[21]

- 俄亥俄州:2003年,该州曾于1868年1月15日撤消了对这一修正案的批准[15][16]

公民与公民权

背景

修正案第一款正式对美利坚合众国公民作出了定义,并保证任何个人的基本权利不会被任何一个州或国家行为限制和剥夺。但在1883年的一组民权案件中,最高法院判定第十四条修正案对个人行为没有约束力,修正案只限针对政府行为,因此没有授权国会立法禁止私人及私人组织的种族歧视行为。[22]

激进派共和党人希望给因第十三条修正案获得自由的人们保障广泛的公民权和人权,但这些权利的范围在修正案生效前就出现了争议[12]:1523。之前国会通过的1866年民权法案认定所有在美利坚合众国出生且受其管辖的人就是美国公民,第十四条修正案的制订者希望将这一原则写入宪法,来防止这一法案被联邦最高法院宣布违宪而被取消,或是被将来的国会通过投票改变[4]:23-24[23]。这一款也是对南方各州以暴力对付黑人行径的回应。国会重建联合委员会认为只有通过一项宪法修正案才能够保护这些州中黑人的权益和福利[24]。

修正案的第一款是该修正案被引用次数最多的部分[25],这条修正案也是宪法中被引用最为频繁的一部分[26]。

公民条款

修正案的这一条款推翻了最高法院在斯科特诉桑福德案中裁决黑人不是也不会成为美国公民并享有各项权利的判决[27][28]。《1866年民权法案》赋予任何生于美国且非外国势力的人公民身份,而第十四条修正案的这一条款则将该规则宪法化。

根据国会对修正案展开的辩论和当时普遍的习惯和认识,对国会通过和各州批准修正案的意图也有着多种不同的诠释。这一条款已经出现的一些主要问题包括:条款在何种情况下包括美洲原住民,非美国公民在美国合法居留期间如果产子,孩子是否可以拥有公民身份,公民权是否可以被剥夺,以及条款是否适用于非法移民。

美洲原住民

国会最初对修正案进行辩论时,公民条款的起草者,密歇根州联邦参议员雅各布·M·霍华德[29]形容该条款虽然与《1866年民权法案》在措辞上有些差异,但内容是相同的。亦即其中排除了美洲原住民,因为他们维持着与部落间的关系,就相当于是“外国大使和或公使的家人”一样,出生在美国,但仍然属于外国人[30]。据西肯塔基大学历史学家格伦·W·拉凡特西(Glenn W. LaFantasie)所说,“有相当数量的资深参议员同意他对公民条款的观点”[29]。其他参议员也同意各国大使或公使的孩童应该被排除[31][32]。

来自威斯康星州的联邦参议员詹姆斯·鲁德·杜利特尔主张所有美洲原住民都受美国管辖,所以使用“未被课税的印第安人”加以明确更为可取[33],但参议院司法委员会主席,伊利诺伊州参议员莱曼·特朗布尔和霍华德对此提出了反驳,他们争辩称联邦政府对美洲原住民部落并没有充分的管辖权,后者属于自我管理,并与合众国签订条约[34][35]。

在1884年的艾尔克诉威尔金斯案中,联邦最高法院裁决于保留地出生的印第安人不属于联邦政府管辖范围,因此不能够获得美国公民身份,亦不可因为之后只是离开保留地并放弃向之前的部落效忠就能成为美国公民[36][37]。这个问题一直到《1924年印第安公民法》通过后才获得解决,该法赋予美洲原住民美国国籍[38]。

他国公民的子女

第十四条修正案规定任何在美国出生的儿童生来就是美国公民,不需考虑其父母的国籍[39]。修正案通过时,包括《1866年民权法案》作者特朗布尔在内的三位参议员以及总统安德鲁·约翰逊都断言,《1866年民权法案》和第十四条修正案都将赋予这样出生的儿童公民权,对此没有参议员提出不同意见[40][41][42]。由于1866年时还不存在非法移民的问题,这些国会议员的意见对于那些合法居留在美国而生下孩子的父母来说是适用的。虽然这以后法律仍然根据出生地原则的标准进行解释,但有些学者对公民权条款是否适用于非法移民留有质疑[39]。时间进入21世纪后,国会曾偶尔讨论过对该条款进行修订,以减少生育旅行现象的出现,这一现象指的是怀有身孕的外国人仕为了让孩子获得美国国籍而进入美国境内进行生育[43]。

在1898年的美国诉黄金德案中,条款中有关合法移民后代公民权的问题受到了考验。最高法院根据第十四条修正案做出判决,拥有中国籍父母而在美国境内出生且拥有一个固定住所,还在美国经商的人,并且他的父母也不是任何外交官的雇员或外国官员,不属任何外国势力时,他就是美国公民[44]。之后一些案件的判决则进一步认定非中国血统的其他同类外籍人仕的后代同样适用这一原则[45]。

失去公民权

只有在以下情况下,美国公民才有可能失去其公民权:

在美国历史上相当长的一段时间里,自愿取得他国国籍将被认为主动放弃其美国公民身份[47],这一规定被写入了当时美国与其他多个国家之间的一系列条约之中(班克罗夫特条约)[48][49][50][51][52]。不过,联邦最高法院在1967年的阿弗罗依姆诉鲁斯克案[53]、1980年的万斯诉特拉查斯案[54]中都否定了这一条款,并认定第十四条修正案的公民条款禁止国会撤消任何美国公民的公民权。但是一个人可以根据他自己的意志来从宪法上放弃自己的公民权,而且国会也可以在赋予一个并非在美国出生的人公民权后,再予以撤消[55]。

特权或豁免权条款

修正案中的特权或豁免权条款规定,“任何一州,都不得制定或实施限制合众国公民的特权或豁免权的法律”,这一条款与宪法第四条的特权和豁免权条款一脉相承[56],后者保护各州公民特权和豁免权不免他州干预[57]。在1873年的屠宰场案中最高法院总结指出宪法承认两种形式的公民,一种是“国家公民”,另一种是“州公民”。法院判决特权或豁免权条款只是禁止各州对国家公民所拥有的特权和豁免权加以干涉[57][58]。法院还认为国家公民的特权和豁免权仅包括那些来自“联邦政府、国民身份、宪法或法律”所赋予的权利[57]。法院确认了为数不多的几项权利,包括使用港口和航道,竞选联邦公职,在公海或外国管辖范围时受联邦政府保护,前往政府所在地,和平集会和向政府请愿,人身保护令特权以及参与政府行政管理的权利[57][58]。这一判决尚未被推翻,而且已经特别受到了几次重申[59]。很大程度上是因为屠宰场案的狭隘判定,这一条款随后已沉寂了一个多世纪[60]。

在1999年的萨恩斯诉罗伊案中,法院判决旅行的权利受到第十四条修正案特权或豁免权的保护[61]。大法官塞缪尔·弗里曼·米勒曾在屠宰场案判决中写道,(通过居住在该州而)成为一个州公民的权利是由宪法中的“那一条”,而不是由正在审议的这个“条款”赋予的[57][62]。

在2010年的麦克唐纳诉芝加哥案中,大法官克拉伦斯·托马斯代表多数意见认为第二修正案保护的个人拥有武器权利同样适用于各州。他宣布自己是根据特权或豁免权条款而非正当程序条款得出了这一结论。兰迪·巴内特曾指出,大法官托马斯的意见是对特权或豁免权条款的“全面恢复”。[63][64]

正当程序条款

第十四条修正案的正当程序条款在文本表述上与第五修正案的同名条款相同,但后者针对的是联邦政府,前者针对的是各州,两个条款都被解读为拥有相同的程序性正当程序和实质性正当程序思想[65]。

程序性正当程序指的是政府应该确保以公正的法律程度来保护公民的生命、自由或财产;实质性正当程序则是指保障公民的基本权利不受政府侵害[66]。第十四条修正案的正当程序条款还融合了权利法案的大部分条文,将这些原本只针对联邦政府的规定通过合并原则应用到各州[67]。

实质性正当程序

从1897年的奥尔盖耶诉路易斯安那州案开始,法院就认为正当程序条款需要向私人契约提供实质性保护,从而禁止政府的各类社会和经济调节、管控,这一原则被称为契约自由原则[68][69]。根据这一原则,法院在1905年的洛克纳诉纽约州案中宣布一项规定面包工人最高工时的法律违宪[70],又于1923年的阿德金斯诉儿童医院案中判决一项规定最低工资标准的法律无效[71],同年的迈耶诉内布拉斯加案中,法院指出“自由”受正当程序条款保护[72][73]。

不过,在1887年的马格勒诉堪萨斯案中,法院支持了一些经济调节政策[74],到了1898年的霍顿诉哈迪案中,法院裁决有关煤矿工人最高工时的法律合宪[75],1908年的穆勒诉俄勒冈州案则认可了规定女性工人最高工时的法律[76]。在1917年的威尔逊诉纽案(Wilson v. New)中,法院认可了总统伍德罗·威尔逊对铁路罢工的干预措施[77],还在1919年的美国诉多雷姆斯案(United States v. Doremus)中认定监管毒品的联邦法院合宪[78]。在1937年的西海岸旅馆公司诉帕里什案案中,法院否定了原本契约自由的广泛认定,但没有明确地将之全盘推翻[79]。

虽然“契约自由”已经失宠,但到了1960年代,法院已经扩展了实质性正当程序的解释,在其中包括了其它未于宪法中列举,但可由现有权利推导出的权利和自由[69]。例如,公正程序条款也是隐私权的宪法基础。最高法院在1965年的格里斯沃尔德诉康涅狄格州案里首次裁决隐私权受宪法保护,由此推翻了康涅狄格州禁止生育控制的法律[80]。由大法官威廉·道格拉斯起草的多数意见认为隐私权可以在权利法案的各项规定中获得支持,大法官阿瑟·戈德堡和约翰·马歇尔·哈伦二世在赞同意见中认为正当程序条款所包括的“自由”包括个人隐私[81]。

隐私权是1973年罗诉韦德案判决的基础,在该案中,最高法院判定得克萨斯州除非是为挽救母亲生命,否则禁止堕胎的法律无效[82]。由大法官哈利·布莱克蒙执笔的多数意见和之前戈德堡与哈伦二世两位大法官在格里斯沃尔德案中的赞同意见一样,认为正当程序条款包括的自由也包括隐私权。这一裁决废止了多个州和联邦对堕胎的限制,成为最高法院历史上最具争议性的判决之一[83]。在1992年的计划生育联盟诉凯西案中,最高法院重申了罗诉韦德案的判决,称“罗诉韦德案判决的核心内容应该予以保留并再次重审”[84][85]。在2003年的劳伦斯诉得克萨斯州案中[86],法院判决得克萨斯州禁止同性性行为的法律违反隐私权[87]。

程序性正当程序

程序性正当程序指的是政府应该确保以公正的法律程序来保护公民的生命、自由或财产,最高法院认为,政府至少应该给予个人知情权,令其可以在听证中给自己辩护,并由一个中立的第三方来进行裁决。例如当政府部门旨在解雇一名雇员,或是从公立学校开除学生,或是停止对某人进行福利救助时,都需要通过以上的程序来进行。[88][89]

法院还根据正当程序原则裁定法官在存在利益冲突时应当予以回避。例如在2009年的卡珀顿诉马西煤炭公司案中,最高法院判定西弗吉尼亚州最高上诉法院的一位大法官应当在一个案件中自行回避,因为案件涉及到他当选该法院法官选举时的一位主要支持者。[90][91]

合并

虽然许多州宪法都是依照联邦宪法和联邦法律制订的,但这些州宪法并不一定包括媲美权利法案的同类规定。在1833年的巴伦诉巴尔的摩案中,最高法院以全体一致通过裁决权利法案只是用来限制联邦政府,对各州无效[92][93]。不过,最高法院之后通过第十四条修正案的正当程序条款将大部分权利法案中的规定应用到各州,这一做法被称为“合并原则”[67]。

对于包括约翰·宾汉姆在内的修正案制定者是否有意建立合并原则的问题,法律史学家一直争论不休[94]。据法律学者阿希尔·里德·阿马所说,第十四条修正案的制定者和早期支持者们相信,在第十四条修正案通过后,各州都将不得不承认与联邦政府相同的个人权利,所有这些权利都很可能被理解成属于修正案中“特权或豁免权”的保障范围[95]。

时间进入20世纪下半叶后,几乎所有权利法案中保障的权利都已经应用到各州[96]。最高法院已经判定第十四条修正案的正当程序条款包含了第一、二、四、六条修正案中的全部条款,还包括第五修正案中除大陪审团条款外的所有内容,以及第八修正案中的残酷和非常惩罚条款[97]。虽然第三条修正案尚未经最高法院应用到各州,但第二巡回上诉法院曾在1982年的英伯朗诉凯里案中将其应用到法院所管辖的几个州中[98]。而第七条修正案有关陪审团审理的权利已经法院裁决不适用于各州[97][99],但其中的重新审查条款不但对联邦法院有效,而且对于“在州法院经陪审团审理并上诉到最高法院的案件”都有效[100]。

平等保护条款

平等保护条款的诞生很大程度上是对实行黑人法令的州中缺乏平等法律保护的回应。根据黑人法令,黑人不能起诉,不能作为证人,也不能给出物证,而且在同等犯罪下,他们受到了惩罚也比白人更严厉[4]:20, 23-24。这一条款规定在同等情况下,个人也应受到同等对待[101]。

虽然第十四条修正案在字面上只是把平等保护条款应用到各州,但最高法院在1954年的波林诉夏普案中认定,这一条款经第五修正案的正当程序条款,可以“反向合并”应用于联邦政府[102][103]。

在1886年的圣克拉拉县诉南太平洋铁路公司案中[104],法庭记者记下了首席大法官莫里森·韦特在判决书批注中的声明:

“法院不希望听到宪法第十四条修正案中有关一州不能在其管辖范围内拒绝给予任何人平等法律保护的规定是否适用于这些公司的争论,我们全部都认为它适用。”[105]

这一判词表明在平等保护条款下公司同样享有与个人一样的平等保护,之后法院多次重申了这一观点[105],并在整个20世纪中占有主流地位,直到包括休戈·布莱克和威廉·道格拉斯在内的大法官提出了质疑[106]。

在第十四条修正案通过后的几十年里,最高法院先是在1880年的斯特劳德诉西弗吉尼亚案中推翻了禁止黑人担任陪审员的法律[107],后又于1886年的益和诉霍普金斯案中裁定歧视美籍华人的洗衣店条例无效,理由均是这些法律/条例违反了平等保护条款[108]。然而到了1896年的普莱西诉弗格森案中,最高法院裁定只要各州可以提供类似的设施,那么就可以在这些设施的基础上实行种族隔离政策,这一隔离被称之为隔离但平等[109][110]。

在1908年的伯利亚学院诉肯塔基州案中,最高法院对平等保护条款增加了进一步的限制,裁定各州可以禁止高校施行黑白同校[111]。到了20世纪初,平等保护条款已经黯然失色,大法官小奥利弗·温德尔·霍姆斯称其是“宪法辩论中万不得已才会使用的最后手段”[112]。

美国最高法院支持的“隔离但平等”超过半个世纪,这一过程中法院已在多个案件里发现各州在隔离情况下分别提供的设施几乎没有均等的。一直到1954年的布朗诉托皮卡教育局案上诉到最高法院后,事情才有了转机。在这个里程碑性质的判决中,最高法院以全体一致的投票结果推翻了普莱西诉弗格森案中有关种族隔离合法的判决。法院认为,即使黑人和白人学校都拥有同等的师资水平,隔离本身对于黑人学生就是一种伤害,因此是违宪的。[113]这一判决受到了南方多个州的强烈抵制,之后长达几十年的时间里,联邦法院一直试图强制执行布朗案的判决,来对抗南方部分州通过各种手段反复试图规避种族融合的作法[114]。联邦法院在全国各地都制订了充满争议的废除种族隔离校车法令并流传下来[115]。在2007年的家长参与社区学校诉西雅图第一学区教育委员会案中,法院裁定家长不能根据种族因素来判断应该把自己的孩子送到哪一所公立学校念书。

在1954年的埃尔南德斯诉得克萨斯州案中,最高法院判决第十四条修正案同样对既非白人,也不是黑人的其他种族和族裔群体提供保护,例如本案中的墨西哥裔美国人[116]。在布朗案之后的半个世纪里,法院将平等保护条款延伸到其他历史上的弱势群体,如女性和非婚生子女,虽然判定这些群体是否受到歧视的标准不如种族歧视那么严格[117][118][119]。

在1978年的加州大学董事会诉巴基案中,最高法院判定公立大学招生中的根据平权法案制订的种族配额政策违反了《1964年民权法案》第6条,但是种族可以作为招生中考虑的一个因素,并且不会违反第6条和第十四条修正案的平等保护条款[120][121]。在2003年的格拉茨诉布林格案和格鲁特诉布林格案里,密歇根大学声称要通过两类向少数族裔提供招生倾斜的政策来实现学校的种族多样性[122][123][124]。在格拉兹案中,法院认为该校以分数为标准的本科招生制度中,为少数族裔加分的做法违反了平等保护条款;而在格鲁兹案里,法院同意该校法学院在招生时,把种族作为确定录取学生的多个考虑因素之一[125]。在2013年的费舍尔诉得州大学案中,法院要求公立学校只有在没有可行的种族中立替代方案时,才能把种族因素纳入招生制度进行考虑[126]。

在1971年的里德诉里德案中,最高法院推翻了爱达荷州偏袒男性的遗嘱认证法律[127],这是最高法院首度裁定任意的性别歧视违反平等保护条款[128]。在1976年的克雷格诉博伦案中,法律判决法定或行政性的性别分类必须接受不偏不倚的司法审查[129][130]。之后,里德和克雷格案成为先例,被多次援引并推翻了多个州的性别歧视法律[128]。

自1964年的韦斯伯里诉桑德斯案和雷诺兹诉西姆斯案开始,法律已经将平等保护条款解读为要求各州按一人一票的原则分摊国会选区和州议会席位[131][132][133][134][135]。法律还在1993年的肖诉里诺案中推翻了以种族为关键考量因素的重新划分选区规划[136],该案中北卡罗莱纳州打算通过这一规划来创造黑人占多数的社区,平衡该州在国会中代表名额不足的情况[137]。

平等保护条款还是2000年布什诉戈尔案判决的基础。该案中最高法院认定没有哪一种宪法认可的方式可以在所需期限内完成对佛罗里达州在2000年美国总统选举中的重新计票[138]。这一判决确保布什最后赢得了这场存在争议的选举[139]。

在2006年的拉丁美洲裔公民联盟诉佩里案中,最高法院裁决众议院多数党领袖汤姆·迪莱的得克萨斯州选区重划方案有意摊薄拉丁裔美国人的选票,因此违反了平等保护条款[140][141]。

众议院议席分摊

修正案的第二款改变了用来确定各州在联邦众议院席位数量的人口统计方式。在修正案通过前,这一方式来自宪法第一条第二款第三节,其中规定“众议员名额和直接税税额,在本联邦可包括的各州中,按照各自人口比例进行分配。各州人口数,按自由人总数加上所有其他人口的五分之三予以确定”[1][3],而第十四条修正案第二款则将最后的“五分之三”去除,改为“众议员名额,应按各州人口比例进行分配,此人口数包括一州的全部人口数”[1][3]。

第二款还规定“一州的年满21岁并且是合众国公民的任何男性居民,除因参加叛乱或其他犯罪外,如其选举权遭到拒绝或受到任何方式的限制,则该州代表权的基础,应按以上男性公民的人数同该州年满21岁男性公民总人数的比例予以削减。”但这一禁令从未被执行,南方各州继续使用各种借口防止许多黑人投票,直到《1965年投票权法》通过后这个问题才得到了解决[142]。此外,由于这一条款只保护了年满21岁男性的投票权,对女性只字未提,所以也成了美国宪法唯一存在明确性别歧视的部分[23]。

有观点认为,第二款已由第十五条修正案废除[143],但最高法院在之后的一些决定中仍然援引了这部分内容。如1974年的理查德森诉拉米瑞兹案中,最高法院援引第2款来作为州剥夺重刑犯投票权的依据[144]。

参与叛乱

第三款规定:“无论何人,凡先前曾以国会议员、或合众国官员、或任何州议会议员、或任何州行政或司法官员的身份宣誓维护合众国宪法,以后又对合众国作乱或反叛,或给予合众国敌人帮助或鼓励,都不得担任国会参议员或众议员、或总统和副总统选举人,或担任合众国或任何州属下的任何文职或军职官员。但国会得以两院各2/3的票数取消此种限制。”[1]:574-575[3][145]。

1975年,国会通过一项联合决议案恢复了美利坚联盟国将军罗伯特·李的公民权[146]。1978年,国会根据第三款去除了针对前南方邦联总统杰佛逊·戴维斯的公职服务禁令[147]。

第三款曾被用来防止美国社会党成员维克多·L·伯格尔当选1919至1920年的联邦众议员,因为他的反军国主义观点被裁定违反了《间谍法》。[148]

公共债务的有效性

第四款确认了国会拨出的所有美国国债的合法性。并确认无论联邦政府还是任何一个州都不会偿还南方邦联因失去奴隶导致的损失以及因对抗北方的战事而欠下的债务。例如南北战争期间,多家英国和法国银行给予邦联巨额贷款,以在战争中支持他们对抗北方[149]。在1935年的佩里诉美国案(Perry v. United States)中,最高法院根据第四款判决一种美国债券失效,并且这一失效已经“超越了国会权利(所能影响的)范围”[150][151]。

2011年的美国债务上限危机对第四款给予总统的权力提出了疑问,截止2013年8月,这个问题仍然没有解决。包括美国财政部长蒂莫西·F·盖特纳、法律学者加勒特·伊普斯(Garrett Epps)、财政专家布鲁斯·巴特利特在内的多人认为债务上限可能是违宪的,所以只要它干扰了政府支付未偿还债券利息和退休金的义务,就应该是无效的[152][153]。

法律分析师杰弗里·罗森曾辩称第四款给予总统单方面授权来提高或忽略国家债务上限,如果到达最高法院,那么裁决将很可能是扩大行政权或是案件因缺乏诉讼资格而遭驳回[154]。加州大学欧文分校法学院教授兼院长欧文·切默林斯基认为即便是有一个“严峻的财政危机”,总统也不能提高债务上限,因为“没有任何一种合理的方式可以从宪法中解读出(允许他这样做的含义)”[155]。

执法权力

第五款也称第十四条修正案执法条款,该条款允许国会通过“适当立法”来实施修正案的规定[156][157]。在1883年的民权案件中,最高法院以狭隘的角度解读第五款,称国会因该条款获得的立法权不能用来进行一般公民权利的立法,而只是作为矫正、补救立法[22]。换言之,法院认为该条款只授权国会立法打击其它几款中规定的侵犯权利行为[158]。

在1966年的卡森巴克诉摩根案中,法院支持了《1965年投票权法》的第4(e)款,其中禁止以通过读写测试为投票先决条件,法院认为这一款是国会对平等保护条款授权的有效行使。法院认为修正案第五款允许国会采取行动补救或预防该修正案保护的权利受到侵害[159][160]。这也是最高法院对第五款给予的一个较为宽泛的解释[161]。但是到了1997年的伯尼市诉弗洛雷斯案中,法院收窄了国会的执法权,称国会不得根据第五款制订对第十四条修正案权利进行实质定义或解读的法律[156][162]。称“任何认为国会在第十四条修正案下拥有其它独立存在且非补救性质权力的意见,本院的判例法均不予支持。[163]”法院裁定,如果国会根据第五款立法保护的公民权利与修正案其它条款“一致和相称”,那么这项立法就是有效的,国会的立法目标应该是防止或补救对这些公民权利的伤害[162]。

联邦最高法院相关案例

公民权

|

|

特权与豁免权

|

|

|

合并原则

|

|

实质性正当程序

|

|

平等保护

|

|

众议院议席分摊

执法权力

|

|

参考资料

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 任东来; 陈伟; 白雪峰; Charles J. McClain; Laurene Wu McClain. 美国宪政历程:影响美国的25个司法大案. 中国法制出版社. 2004-01. ISBN 7-80182-138-6.

- ↑ Constitution of the United States: Amendments 11–27. National Archives and Records Administration. [2013-09-03].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 李道揆. 美国政府和美国政治(下册). 北京: 商务印书馆. 1999: 775–799. ISBN 9787100025294.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Goldstone, Lawrence. Inherently Unequal: The Betrayal of Equal Rights by the Supreme Court, 1865–1903. Walker & Company. 2011. ISBN 978-0-8027-1792-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Stromberg, Joseph R. A Plain Folk Perspective on Reconstruction, State-Building, Ideology, and Economic Spoils. Journal of Libertarian Studies. 2002 Spring.

- ↑ Nelson, William E. The Fourteenth Amendment: From Political Principle to Judicial Doctrine. Harvard University Press. 1988: 47. ISBN 978-0-674-04142-4.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. HarperCollins. 1988. ISBN 978-0-06-203586-8.

- ↑ Rosen, Jeffrey. The Supreme Court: The Personalities and Rivalries That Defined America. MacMillan. 2007: 79.

- ↑ Newman, Roger. The Constitution and its Amendments 4. Macmillan. 1999: 8.

- ↑ Soifer, Aviam. Federal Protection, Paternalism, and the Virtually Forgotten Prohibition of Voluntary Peonage (PDF) 112 (7). Columbia Law Review: 1614. 2012-11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Carter, Dan. When the War Was Over: The Failure of Self-Reconstruction in the South, 1865-1867. LSU Press. 1985: 242–243.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Graber, Mark A. Subtraction by Addition? The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments (PDF) 112 (7). Columbia Law Review: 1501–1549. 2012-11.

- ↑ The Civil War And Reconstruction. [2012-10-20].

- ↑ Library of Congress, Thirty-Ninth Congress Session II. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Amendment XIV. US Government Printing Office. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Mount, Steve. Ratification of Constitutional Amendments. 2007-01 [2013-09-04].

- ↑ Documentary History of the Constitution of the United States, Vol. 5. Department of State. : 533–543. ISBN 0-8377-2045-1.

- ↑ A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875. Library of Congress. : 707 [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Killian, Johnny H.; et al. The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation: Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 28, 2002. Government Printing Office. : 31. ISBN 9780160723797.

- ↑ Chin, Gabriel J.; Abraham, Anjali. Beyond the Supermajority: Post-Adoption Ratification of the Equality Amendments. Arizona Law Review. 2008, 50: 25 [2013-09-04].

- ↑ P.L. 2003, Joint Resolution No. 2; 4/23/03

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Eric Foner. In These Times. Jonathan Birnbaum; Clarence Taylor (编). The Second American Revolution. Civil Rights Since 1787. New York University Press. 1987-09. ISBN 0814782493.

|year=与|date=不匹配 (帮助) - ↑ Finkelman, Paul, John Bingham and the Background to the Fourteenth Amendment. Akron Law Review, Vol. 36, No. 671, 2003 (Ssrn.com). 2009-04-02. SSRN 1120308

.

.

- ↑ Harrell, David; Gaustad, Edwin. Unto A Good Land: A History Of The American People 1. Eerdmans Publishing. 2005: 520.

The most important, and the one that has occasioned the most litigation over time as to its meaning and application, was Section One.

- ↑ Stephenson, D. The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. 2003-11-12: 147 [2013-09-04]. ISBN 978-1576078297.

- ↑ Tsesis, Alexander, The Inalienable Core of Citizenship: From Dred Scott to the Rehnquist Court. Arizona State Law Journal, Vol. 39, 2008 (Ssrn.com). SSRN 1023809

.

.

- ↑ McDonald v. Chicago, 130 S. Ct. 3020, 3060 (2010) ("This [clause] unambiguously overruled this Court's contrary holding in Dred Scott.")

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 LaFantasie, Glenn. The erosion of the Civil War consensus. Salon. 2011-03-20.

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, p. 2893. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

Senator Reverdy Johnson said in the debate: "Now, all this amendment provides is, that all persons born in the United States and not subject to some foreign Power--for that, no doubt, is the meaning of the committee who have brought the matter before us--shall be considered as citizens of the United States...If there are to be citizens of the United States entitled everywhere to the character of citizens of the United States, there should be some certain definition of what citizenship is, what has created the character of citizen as between himself and the United States, and the amendment says citizenship may depend upon birth, and I know of no better way to give rise to citizenship than the fact of birth within the territory of the United States, born of parents who at the time were subject to the authority of the United States."

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, p. 2897. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 1, p. 572. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 11 Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, pp. 2890,2892-4,2896. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, p. 2893. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

Trumbull, during the debate, said, "What do we [the committee reporting the clause] mean by 'subject to the jurisdiction of the United States'? Not owing allegiance to anybody else. That is what it means." He then proceeded to expound upon what he meant by "complete jurisdiction": "Can you sue a Navajoe Indian in court?...We make treaties with them, and therefore they are not subject to our jurisdiction.... If we want to control the Navajoes, or any other Indians of which the Senator from Wisconsin has spoken, how do we do it? Do we pass a law to control them? Are they subject to our jurisdiction in that sense?.... Would he [Sen. Doolittle] think of punishing them for instituting among themselves their own tribal regulations? Does the Government of the United States pretend to take jurisdiction of murders and robberies and other crimes committed by one Indian upon another?... It is only those persons who come completely within our jurisdiction, who are subject to our laws, that we think of making citizens."

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, p. 2895. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

Howard additionally stated the word jurisdiction meant "the same jurisdiction in extent and quality as applies to every citizen of the United States now" and that the U.S. possessed a "full and complete jurisdiction" over the person described in the amendment.

- ↑ Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884)

- ↑ Urofsky, Melvin I.; Finkelman, Paul. A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States 1 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-19-512635-1.

- ↑

Reid, Kay. Multilayered loyalties: Oregon Indian women as citizens of the land, their tribal nations, and the united States. Oregon Historical Quarterly. – via HighBeam Research

. 2012-09-22 [2013-09-04].

. 2012-09-22 [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Lee, Margaret. Birthright Citizenship Under the 14th Amendment of Persons Born in the United States to Alien Parents (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 2010-08-12 [2013-09-04].

Over the last decade or so, concern about illegal immigration has sporadically led to a re-examination of a long-established tenet of U.S. citizenship, codified in the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and §301(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) (8 U.S.C. §1401(a)), that a person who is born in the United States, subject to its jurisdiction, is a citizen of the United States regardless of the race, ethnicity, or alienage of the parents. [...] "some scholars argue that the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment should not apply to the children of unauthorized aliens because the problem of unauthorized aliens did not exist at the time the Fourteenth Amendment was considered in Congress and ratified by the states.

参数|quote=值左起第275位存在换行符 (帮助) - ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 1, p. 498. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

The debate on the Civil Rights Act contained the following exchange:

Mr. Cowan: "I will ask whether it will not have the effect of naturalizing the children of Chinese and Gypsies born in this country?"

Mr. Trumbull: "Undoubtedly."

...

Mr. Trumbull: "I understand that under the naturalization laws the children who are born here of parents who have not been naturalized are citizens. This is the law, as I understand it, at the present time. Is not the child born in this country of German parents a citizen? I am afraid we have got very few citizens in some of the counties of good old Pennsylvania if the children born of German parents are not citizens."

Mr. Cowan: "The honorable Senator assumes that which is not the fact. The children of German parents are citizens; but Germans are not Chinese; Germans are not Australians, nor Hottentots, nor anything of the kind. That is the fallacy of his argument."

Mr. Trumbull: "If the Senator from Pennsylvania will show me in the law any distinction made between the children of German parents and the children of Asiatic parents, I may be able to appreciate the point which he makes; but the law makes no such distinction; and the child of an Asiatic is just as much of a citizen as the child of a European." - ↑ Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, pp. 2891-2. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-04].

During the debate on the Amendment, Senator John Conness of California declared, "The proposition before us, I will say, Mr. President, relates simply in that respect to the children begotten of Chinese parents in California, and it is proposed to declare that they shall be citizens. We have declared that by law [the Civil Rights Act]; now it is proposed to incorporate that same provision in the fundamental instrument of the nation. I am in favor of doing so. I voted for the proposition to declare that the children of all parentage, whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal Civil Rights with other citizens."

- ↑ Andrew Johnson. Veto of the Civil Rights Bill. teachingamericanhistory.org. [2013-09-04].

- ↑ 14th Amendment: why birthright citizenship change 'can't be done'. Christian Science Monitor. 2010-08-10 [2013-09-04].

- ↑ United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898)

- ↑ Rodriguez, C.M. "The Second Founding: The Citizenship Clause, Original Meaning, and the Egalitarian Unity of the Fourteenth Amendment" [PDF] (PDF). U. Pa. J. Const. L. 2009, 11: 1363–1475 [2011-07-15].

- ↑ U.S. Department of State. Advice about Possible Loss of U.S. Citizenship and Dual Nationality. 2008-02-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ For example, see Perez v. Brownell, 356 U.S. 44 (1958), overruled by Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967)

- ↑ For the text of the first Bancroft treaties see Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States 1776-1949 (compiled under the direction of Charles. I. Bevans), VIII (Germany-Iran), Washington, DC: The Department of State, Government Printing Office, 1971

- ↑ See Oppenheim, Lassa, International Law, A Treatise, I (Peace), London, New York, Bombay: Longmans, Green, Co.: 368, 1905

- ↑ See Munde, Charles, The Bancroft Naturalization Treaties with the German States; The United States Constitution and the Rights and Privileges of Citizens of Foreign Birth; Being a Collection of Documents and Opinions Relating to the Subject, to the Encroachment of the North-German Treaty on Our Civil Rights, and the Measures to Rebut it; An Appeal to the German-American Citizens, to the Government, Congress, Court of Claims, and the People of the United States of America, Würzburg: A. Stuber, 1868

- ↑ There were bilateral treaties with Albania, Austria-Hungary, Baden, Bavaria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Brazil, Costa Rica, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, El Salvador, Haiti, Hesse, Honduras, Lithuania, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Prussia, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Uruguay and Wurttemberg. For the text of the treaty with Great Britain see Convention between the United States of America and Great Britain, Relative to Naturalization, Concluded May 13, 1870, Ratifications Exchanged August 10, 1870, Proclaimed by the President of the United States, September 16, 1870, Treaties and Convention between the United States and Other Powers, Since July 4, 1776, Revised Edition, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office: 405, 1873 . Norway and Sweden were included in a single treaty signed in 1869 when the two countries were joined in a personal union under the Swedish monarchy. The Interamerican Convention of 1906 covered Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Panama and Uruguay. For the text of the 1906 Inter-American Convention see Status of Naturalized Persons who Return to Country Of Origin (Inter-American), Convention signed at Rio de Janeiro, August 13, 1906, Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States 1776-1949 (compiled under the direction of Charles. I. Bevans), 1 (Multilateral) 1776-1917, Washington, DC: The Department of State, Government Printing Office: 544, 1968 . The treaties with each of the German states except Prussia became obsolete when the German Empire was proclaimed in 1871. The treaties with Prussia and Austria-Hungary lapsed with the American declaration of war in 1917 and were never revived. Brazil, Mexico and the United Kingdom terminated their treaties; and Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay withdrew from the 1906 convention.

- ↑ For the 1937 Treaty with Lithuania see Liability for Military Service of Naturalized Persons and Persons born with Double Nationality, Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States 1776-1949 (compiled under the direction of Charles. I. Bevans), IX (Iraq-Muscat), Washington, DC: The Department of State, Government Printing Office: 690, 1972

- ↑ Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967)

- ↑ 444 U.S. 252 (1980)

- ↑ Yoo, John. Survey of the Law of Expatriation: Memorandum Opinion for the Solicitor General. justice.gov. 2002-06-12 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Berger, Raoul. Government by Judiciary : The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. 1997: 58 [2013-09-05]. ISBN 0865971447.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873)

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Beatty, Jack. Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900. New York: Vintage Books. 2008-04-08: 135. ISBN 1400032423.

- ↑ e.g., United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000)

- ↑ Shaman, Jeffrey M. Constitutional Interpretation: Illusion and Reality. Praeger. 2000-11-30: 248. ISBN 978-0313314735.

- ↑ Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489 (1999), quote:Despite fundamentally differing views concerning the coverage of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, most notably expressed in the majority and dissenting opinions in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), it has always been common ground that this Clause protects the third component of the right to travel. Writing for the majority in the Slaughter-House Cases, Justice Miller explained that one of the privileges conferred by this Clause "is that a citizen of the United States can, of his own volition, become a citizen of any State of the Union by a bona fide residence therein, with the same rights as other citizens of that State." (emphasis added)

- ↑ Bogen, David. Privileges and Immunities: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution. Praeger. 2003-04-30: 104 [2013-09-05]. ASIN B001ECQKR0.

- ↑ McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 3025 (2010)

- ↑ Barnett, Randy. Privileges or Immunities Clause alive again. SCOTUSblog. 2010-06-28 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Curry, James A.; Riley, Richard B.; Battiston, Richard M. 6. Constitutional Government: The American Experience. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. 2003: 210. ISBN 0-7872-9870-0.

- ↑ Gupta, Gayatri. Due process. Folsom, W. Davis; Boulware, Rick (编). Encyclopedia of American Business. Infobase: 134. 2009.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Cord, Robert L. The Incorporation Doctrine and Procedural Due Process Under the Fourteenth Amendment: An Overview (PDF). Brigham Young University Law Review. 1987, (3): 868 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165 U.S. 578 (1897)

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Due Process of Law – Substantive Due Process. West's Encyclopedia of American Law. Thomson Gale. 1998 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905)

- ↑ Adkins v. Children's Hospital, 261 U.S. 525 (1923)

- ↑ Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923)

- ↑ CRS Annotated Constitution. Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute. [2013-06-12].

[w]ithout doubt...denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

- ↑ Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U.S. 623 (1887)

- ↑ Holden v. Hardy, 169 U.S. 366 (1898)

- ↑ Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908)

- ↑ Wilson v. New, 243 U.S. 332 (1917)

- ↑ United States v. Doremus, 249 U.S. 86 (1919)

- ↑ West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937)

- ↑ Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- ↑

Griswold v. Connecticut. Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)

- ↑

Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973) Doe v. Bolton 410 U.S. 179 (1973). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992)

- ↑ 505 U.S. 845 (1992), 505 U.S. 846 (1992)

- ↑ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)

- ↑

Spindelman, Marc. Surviving Lawrence v. Texas. Michigan Law Review. – via HighBeam Research

. 2004-06-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2004-06-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ White, Bradford. Procedural Due Process in Plain English. National Trust for Historic Preservation. 2008. ISBN 0-89133-573-0.

- ↑ See also Mathews v. Eldridge (1976), 424 U.S. 319 (1976)

- ↑ Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., 556 U.S. ___ (2009)

- ↑ Jess Bravin and Kris Maher. Justices Set New Standard for Recusals. The Wall Street Journal. 2009-06-08 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. 243 (1833)

- ↑

Levy, Leonard W. Barron v. City of Baltimore 7 Peters 243 (1833). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research

. [2013-09-05].

. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Foster, James C. Bingham, John Armor. Finkleman, Paul (编). Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties. CRC Press: 145. 2006.

- ↑ Amar, Akhil Reed. The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment. Yale Law Journal (The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 101, No. 6). 1992, 101 (6): 1193–1284 [2013-09-05]. JSTOR 796923. doi:10.2307/796923.

- ↑ Duncan v. Louisiana (Mr. Justice Black, joined by Mr. Justice Douglas, concurring). Cornell Law School – Legal Information Institute. 1968-05-20 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Levy, Leonard. Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights: The Incorporation Theory (American Constitutional and Legal History Series). Da Capo Press. 1970. ISBN 0-306-70029-8.

- ↑ Engblom v. Carey, 677 F.2d 957 (1982)

- ↑ Minneapolis & St. Louis R. Co. v. Bombolis (1916). Supreme.justia.com. 1916-05-22 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis, and Interpretation - 1992 Edition --> Amendments to the Constitution --> Seventh Amendment - Civil Trials. U.S. Government Printing Office. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1464. 1992 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Failinger, Marie. Equal protection of the laws. Schultz, David Andrew (编). The Encyclopedia of American Law. Infobase: 152–153. 2009.

- ↑ Primus, Richard. Bolling Alone. Columbia Law Review. 2004-05 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)

- ↑ 118 U.S. 394 (1886)

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Johnson, John W. Historic U.S. Court Cases: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2001-01-01: 446–447. ISBN 978-0-415-93755-9.

- ↑ Vile, John R. (编). Corporations. Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues: 1789 - 2002. ABC-CLIO: 116. 2003.

- ↑ Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)

- ↑ Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)

- ↑ Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

- ↑ Abrams, Eve. Plessy/Ferguson plaque dedicated. WWNO (University New Orleans Public Radio). 2009-02-12 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908)

- ↑ Holmes, Oliver Wendell, Jr. 274 U.S. 200: Buck v. Bell. Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute. [2013-06-12].

- ↑ Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

- ↑ Patterson, James. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy (Pivotal Moments in American History). Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-19-515632-3.

- ↑ Forced Busing and White Flight. Time. 1978-09-25 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954)

- ↑ United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996)

- ↑ Levy v. Louisiana, 361 U.S. 68 (1968)

- ↑ Gerstmann, Evan. The Constitutional Underclass: Gays, Lesbians, and the Failure of Class-Based Equal Protection. University Of Chicago Press. 1999. ISBN 0-226-28860-9.

- ↑ Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978)

- ↑

Supreme Court Drama: Cases That Changed America. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke 1978. Supreme Court Drama: Cases that Changed America. – via HighBeam Research

. 2001 [2013-09-05].

. 2001 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003)

- ↑ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003)

- ↑ Alger, Jonathan. Grutter/Gratz and Beyone: the Diversity Leadership Challenge. University of Michigan. 2003-10-11 [2013-09-05].

- ↑

Eckes, Susan B. Race-Conscious Admissions Programs: Where Do Universities Go From Gratz and Grutter?. Journal of Law and Education. – via HighBeam Research

. 2004-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2004-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Howe, Amy. Finally! The Fisher decision in Plain English. SCOTUSblog. 2013-06-24 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971)

- ↑ 128.0 128.1

Reed v. Reed 1971. Supreme Court Drama: Cases that Changed America. – via HighBeam Research

. 2001-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2001-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976)

- ↑

Karst, Kenneth L. Craig v. Boren 429 U.S. 190 (1976). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964)

- ↑ Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 .

- ↑ Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)

- ↑ Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 .

- ↑ Epstein, Lee; Walker, Thomas G. Constitutional Law for a Changing America: Rights, Liberties, and Justice 6th. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. 2007: 775. ISBN 0-87187-613-2.

Wesberry and Reynolds made it clear that the Constitution demanded population-based representational units for the U.S. House of Representatives and both houses of state legislatures....

- ↑ Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993)

- ↑ Aleinikoff, T. Alexander; Samuel Issacharoff. Race and Redistricting: Drawing Constitutional Lines after Shaw v. Reno. Michigan Law Review (Michigan Law Review, Vol. 92, No. 3). 1993, 92 (3): 588–651. JSTOR 1289796. doi:10.2307/1289796.

- ↑ Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000)

- ↑ Bush v. Gore. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006)

- ↑

Daniels, Gilda R. Fred Gray: life, legacy, lessons. Faulkner Law Review. – via HighBeam Research

. 2012-03-22 [2013-09-05].

. 2012-03-22 [2013-09-05].

- ↑

Friedman, Walter. Fourteenth Amendment. Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. – via HighBeam Research

. 2006-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2006-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Chin, Gabriel J. Reconstruction, Felon Disenfranchisement, and the Right to Vote: Did the Fifteenth Amendment Repeal Section 2 of the Fourteenth?. Georgetown Law Journal. 2004, 92: 259.

- ↑ Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974)

- ↑ Sections 3 and 4: Disqualification and Public Debt. Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. 1933-06-05 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Pieces of History: General Robert E. Lee's Parole and Citizenship. Prologue Magazine (The National Archives). 2005, 37 (1) [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Goodman, Bonnie K. History Buzz: October 16, 2006: This Week in History. History News Network. 2006 [2009-09-08].

17/10/1978 - Pres Carter signs bill restoring Jefferson Davis citizenship

- ↑ Chapter 157: The Oath As Related To Qualifications, Cannon's Precedents of the U.S. House of Representatives 6, 1936-01-01, 6 [2013-09-05]

- ↑ SECTIONS 3 AND 4. DISQUALIFICATION AND PUBLIC DEBT. Findlaw.com. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Perry v. United States294 U.S. 330 (1935)

- ↑ 294 U.S. 330 at 354. Findlaw.com. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Our National Debt 'Shall Not Be Questioned,' the Constitution Says. The Atlantic. 2011-05-04 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Sahadi, Jeanne. Is the debt ceiling unconstitutional?. CNN Money. 2011-07-07 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Rosen, Jeffrey. How Would the Supreme Court Rule on Obama Raising the Debt Ceiling Himself?. The New Republic. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Chemerinsky, Erwin. The Constitution, Obama and raising the debt ceiling. Los Angeles Times. 2013-09-05 [2011-07-30].

- ↑ 156.0 156.1

Engel, Steven A. The McCulloch theory of the Fourteenth Amendment: City of Boerne v. Flores and the original understanding of section 5. Yale Law Journal. – via HighBeam Research

. 1999-10-01 [2013-09-05].

. 1999-10-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Kovalchick, Anthony. Judicial Usurpation of Legislative Power: Why Congress Must Reassert its Power to Determine What is Appropriate Legislation to Enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. Chapman Law Review. 2007-02-15, 10 (1) [2013-09-05].

- ↑ FindLaw: U.S. Constitution: Fourteenth Amendment, p. 40. Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966)

- ↑

Eisenberg, Theodore. Katzenbach v. Morgan 384 U.S. 641 (1966). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-05].

- ↑ FindLaw: U.S. Constitution: Fourteenth Amendment, p. 40. Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. [2013-09-05].

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997)

- ↑ ''City of Boerne v. Flores'', Opinion of the Court, Part III-A-3. Supct.law.cornell.edu. 1997-06-25 [2013-09-05].

扩展阅读

- William E. Nelson. The Fourteenth Amendment: from political principle to judicial doctrine. Harvard University Press. 1998-08-11 [2013-09-05]. ISBN 978-0674316263.

- Bogen, David S. Privileges and Immunities: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2003-04-30. ISBN 9780313313479.

- Halbrook, Stephen P. Freedmen, the 14th Amendment, and the Right to Bear Arms, 1866-1876. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1998. ISBN 9780275963316. at Questia [1]

- Bogen, David S. Privileges and Immunities: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2003-04-30. ISBN 9780313313479.

- Annotated Constitution. Cornell University Law School. [2013-09-01].

- Primary Documents in American History: 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Library of Congress. 2012-08-24 [2013-09-05].

外部链接

- Amendments to the Constitution of the United States (PDF). GPO Access.(PDF格式,提供有修正案和批准日期的文本内容)

- 国家档案馆上第11至第27条修正案的原文页面