| 麦角菌属 | |

|---|---|

| |

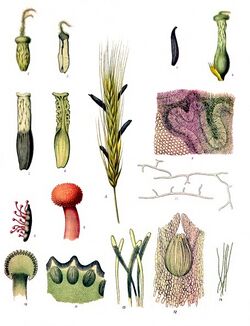

| 《科勒药用植物》(1897), Claviceps purpurea | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 真菌界 Fungi |

| 门: | 子囊菌门 Ascomycota |

| 纲: | 粪壳菌纲 Sordariomycetes |

| 目: | 肉座菌目 Hypocreales |

| 科: | 麦角菌科 Clavicipitaceae |

| 属: | 麦角菌属 Claviceps Tul. & C. Tul. 1853 |

| 种 | |

|

约50种, 包括: | |

麦角是谷类作物(如小麦)被真菌感染所形成的黑色子实体。它是由多种叫做麦角菌的真菌引起的。人或牲畜食用带有麦角的谷物会造成幻觉、痉挛、精神错乱、四肢疼痛、如火焚身等症状,中世纪曾在欧洲造成大规模不知名瘟疫,称为“圣安东尼之火”(Saint Anthony’s fire)。1938年瑞士化学家艾伯特·霍夫曼由麦角酸中合成出麦角二乙胺(LSD),找出了麦角造成幻觉的原因。

-

雀麦上的麦角

-

麦穗上的麦角

-

混在谷物中的麦角

-

麦角中毒患者,《圣安东尼的诱惑》局部,格吕内瓦德绘,1515年

病征

被麦角菌感染后的第一个明显症状是出现“蜜露(honeydew)”,是一种粘性的黄色含糖溶液,是由受感染的黑麦颖片汁液和分生孢子组成,最终会被紫黑色菌核代替,成为麦角。菌核的大小取决于寄主植物。它通常是宿主种子的1至5倍。因此,在黑麦等大种子的谷物中发现了最大的麦角(1-5厘米,0.4-2英寸)。菌核由含有储存细胞的白色菌丝体组织和深色的皮质外层组成,可保护真菌菌丝体免受干燥,紫外线和其他不利环境的影响。

病原生理学

有性世代

有性生殖由雌性产囊体(ascogonium)和雄性藏精器(antheridium)融合形成二倍体核,然后减数分裂返回单倍体状态。有性生殖所产生的有性子实体称为子囊壳(perithecium),里面含多个子囊(asci),每个子囊壳都包含8个丝状子囊孢子,其直径最大为2 µm,长度为60-70 µm。子囊孢子从子囊和子囊壳喷出到空气中(7-15厘米高),并通过气流或昆虫传播。每个菌核产生多达一百万个子囊孢子。只有落在宿主植物柱头或子房上的那些子囊孢子才能引起感染。草花的柱头很大,像羽毛一样,可以捕获风中花粉。这个相同的功能会捕获空中的子囊孢子。子囊孢子是主要的(初始)接种物。

无性世代

发芽的子囊孢子产生长丝状菌丝,缠据在寄主植物花的子房中。随着菌丝越来越长越来越多,菌丝体在含糖的淡黄色黏稠的蜜露中由栅状分生孢子梗(palisade conidiophores)产生的无性分生孢子(asexual conidia),形成二次接种原(secondary inoculum)。蜜露能将昆虫吸引到风传花的花朵上,受分生孢子污染的昆虫可能会拜访健康的花朵,并开始新的感染。飞溅的雨滴也有助于分生孢子的散布。来自麦角感染野草的分生孢子可能是谷物和草籽生产区域的主要接种物(inoculum)。随着时间的推移,菌丝会消耗整个子房,并且菌丝的线会变粗并交织在一起。同时,分生孢子和蜜露生产停止。不断增长的菌丝之间的相互压力会导致致密的致密组织块(称为假薄壁组织)的产生,最终形成坚硬,深色的菌核或麦角。

病害循环

病原菌以菌核(sclerotium)或麦角为残存或越冬结构。在收获时,一小部分菌核与谷物一起被收获,另一部分则落在地面上。菌核处于休眠状态,直到它们处于有利的天气条件下。发芽前菌核的春化需要4至8周的0 – 10 °C温度。菌核在春季发芽,刚好在谷类和禾本科植物中开花之前发芽,并产生有柄的球形子座(stroma),子座边原形成子囊壳,里面有许多子囊,子囊孢子再度感染黑麦的子房。

流行病学

由于Claviceps purpurea的菌核萌发需要低温,因此在温暖的气候下,例如美国东南部,菌核常被其他真菌缠据,不能很好地存活。子座发芽和子囊孢子的产生需要降雨或高土壤湿度,在谷物和许多草中,受精后对感染的抵抗力增强。因此,当遇到延迟或干扰授粉的情况(例如凉爽,潮湿的天气)会增加易感性。分生孢子是二次传播的重要手段,从受感染到健康花朵的任何蜜露的转移都可能导致感染,可通过将分生孢子转移到健康花朵上的任何方式进行,包括雨溅,昆虫和移动设备。

疾病管理

清洁种子:可以通过重力梯度的清洁设备或在盐水中浮选(例如20%的盐溶液)从谷物中去除大部分麦角。

使用干净种子:目前尚无针对麦角菌的有效种子处理方法,因此只能种植无麦角的种子。使用认证种子可以大大减少种植麦角感染种子的风险。

环境卫生:去除田间内外的野草、杂草,这些杂草可能是越冬菌核的麦角接种物的第一个来源,或者如果是在作物开花前产生的,则可以作为蜜露的来源。

轮作:由于麦角菌(菌核菌)通常不能存活超过一年,因此种植非寄主植物的轮作是一年生作物的可行管理策略。

深耕:如果菌核通过深耕掩埋在土壤中,则地层中的子囊子不能排放到空气中。但尽管深耕可以掩埋麦角,现在许多谷物作物都采用“免耕”种植方式,将新作物直接播种到先前作物的秸秆中,以减少土壤侵蚀。当不进行深耕时,轮作更为重要。

收成技术:麦角通常在田间边缘处更为严重,因为孢子是由风和活跃的昆虫从路边的草中运出的。收获前,应先对田间进行筛选以确定感染严重的地区,并应分别收获这些地区的植物。

田间焚烧:麦角是草种子生产中最重要的疾病之一,由于许多草是多年生草种,因此耕作和轮作不是管理选择。自1940年代以来,美国西北部一直在进行收获后田间焚烧,以管理麦角菌和其他疾病及害虫,但由于对环境的关注,立法对焚烧进行了限制。

历史意义

麦角(Ergot)词源于拉丁词articulum,源于古法语argot(cockspur,暗示了真菌的菌核形状,因为法国人注意到菌核和公鸡腿上的马刺之间有些相似之处,在欧洲中世纪,麦角菌引起的疾病被称为圣安东尼大火或圣火,在重大疫情中,据报告死亡率在10%至20%之间。在了解这种疾病之前,麦芽和黑麦谷物一起被磨碎,并在面粉烘烤时被摄入。症状还取决于所摄入麦角中存在的毒素(或生物碱)的浓度和浓度,麦角毒症主要有两种临床毒性形式:坏疽和抽搐,常见症状包括奇怪的精神异常、幻觉、皮肤灼热或昆虫在皮下爬行的感觉。一些受害者由于四肢血管收缩而导致坏疽。许多受害者失去了手脚。患有麦角病的患者在圣安东尼的医院得到照顾,直到不再遭受长期痛苦为止。

参考资料

Agrios, G. N. 2005. Plant Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier–Academic Press, Boston.

Bandyopadhyay, R., Frederickson, D. E., McLaren, N.W., Odvody, G. N., and Ryley, M. L. 1998. Ergot: A new disease threat to sorghum in the Americas and Australia. Plant Dis. 82:356-367.

Blaney, B. J., Kopinski, J. S., Magee, M. H., McKenzie, R. A., Blight, G. W., Maryam, R., and Downing, J. A. 2000. Blood prolactin depression in growing pigs fed sorghum ergot (Calviceps africana). Aus. J. Agri. Res. 51:758-791.

Bové, F. J. 1970. The Story of Ergot. S. Karger, New York.

Caporael, L. R. 1976. Ergotism: The Satan loosed in Salem? Science 192:21-26.

Carefoot, G. L., and Sprott, E. R. 1967. Famine on the Wind. Rand McNally, Chicago.

Esser, K., and Düvell, A. 1984. Biotechnological exploitation of the ergot fungus (Claviceps purpurea). Process Biochem. 19:142-149.

Evans, I. R., Maurice, D. C., Penney, D. C., and Solberg, E. D. 1993-1994. Wheat diseases and copper nutrition. Better Crops, pp. 6–8.

Graham, R. D. 1975. Male sterility in wheat plants deficient in copper. Nature 254:514-515.

Guerre, P. 2015. Ergot alkaloids produced by endophytic fungi of the genus Epichloe. Toxins 7:773-790.

Hudler, G. W. 1998. Magical Mushrooms, Mischievous Molds. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Johnston, W. J., Golob, C. T., Sitton, J. W., and Schultz, T. R. 1996. Effect of temperature and postharvest field burning of Kentucky bluegrass on germination of sclerotia of Claviceps purpurea. Plant Dis. 80:766-768.

Kirby, H. W. 1998. Ergot of cereals and grasses. University of Illinois Extension. RPD No. 107. https://ipm.illinois.edu/diseases/rpds/107.pdf

Kopinski, J. S., Blaney, B. J., Murray, S. A., and Downing, J. A. 2008. Effect of feeding sorghum ergot (Claviceps africana) to sows during mid lactation on plasma prolactin and litter performance. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 92:554-561.

Kren, V., and Cvak, L., eds. 1999. Ergot: The Genus Claviceps. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Kuldau, G., and Bacon, C. 2008. Clavicipitaceous endophytes: Their ability to enhance resistance of grasses to multiple stresses. Biol. Control. 46:57-71.

Lee, M. R. 2009. The history of ergot of rye (Claviceps purpurea) I: From antiquity to 1900. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 39:179-184.

Lorenz, K. 1979. Ergot on cereal grains. CRC Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 11:311-354.

Mathre, D. E., ed. 1997. Compendium of Barley Diseases. 2nd ed. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN.

Matossian, M. K. 1989. Poisons of the Past. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Miedaner, T., and Geiger, H. H. 2015. Biology, genetics, and management of ergot (Claviceps spp.) in rye, sorghum, and pearl millet. Toxins 7:659-678.

Odvody, G., Bandyopadhyay, R., Frederiksen, R. A., Isakeit, T., Frederickson, D., Kaufman, H., Dahlberg, J., Velasquez, R. and Torres, H. 1998. Sorghum ergot goes global in less than three years. APS Features. doi:10.1094/APSFeature-1998-06.

Puranik, S. B., and Mathre, D. E. 1971. Biology and control of ergot on male sterile wheat and barley. Phytopathology 61:1075-1080.

Rehacek, Z., and Sajdl, P. 1993. Ergot Alkaloids: Chemistry, Biological Effects, Biotechnology. Elsevier, New York.

Schardl, C. L., and Phillips, T. D. 1997. Protective grass endophytes: Where are they from and where are they going? Plant Dis. 81:430-438.

Schlegel, R. H. J. 2014. Rye: Genetics, Breeding, and Cultivation. CRC Press–Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL.

Schultz, T. R., Johnston, W. J., Golob, C. T., and Maguire, J. D. 1993. Control of ergot in Kentucky bluegrass seed production using fungicides. Plant Dis. 77:685-687.

Spanos, N., and Gottlieb, J. 1976. Ergotism and the Salem Village Witch Trials. Science. 194:1390-1394.

Thakur, R. P., and King, S. B. 1988. Ergot disease of pearl millet. Information Bull. No. 24. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Patancheru, India.

Tudzynski, P., and Scheffer, J. 2004. Claviceps purpurea: Molecular aspects of a unique pathogenic lifestyle. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5:377-388.

Uppala, S., Wu, B. M., and Alderman, S. C. 2016. Effects of temperature and duration of preconditioning cold treatment on sclerotial germination of Claviceps purpurea. Plant Dis. 100:2080-2086.

Wegulo, S. N., and Carlson, M. P. 2011. Ergot of small grain cereals and grasses and its health effects on humans and livestock. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. EC 1880. http://extensionpubs.unl.edu/publication/9000016368209/ergot-of-small-grain-cereals-and-grasses-and-its-health-effects-on-humans-and-livestock/

Wood, G., and Coley-Smith, J. R. 1982. Epidemiology of ergot disease (Claviceps purpurea) in open-flowering male sterile cereals. Ann. Appl. Biol. 100:73-82.